By ELIZABETH COLUCCIO

Mornings are very bad at the grandparents’ house. Early morning peace is interrupted by a low groaning from the narrow hospital bed that now resides in what used to be a spare bedroom. My grandfather, Carmine Angotti, who turned 84 this year, lies curled up like a child against the bars of the bed, and he doesn’t want to get up.

My grandmother asked me to come help her before I went to class because she had dismissed the home care aide, and she couldn’t lift him on her own. Not only is he a good head and shoulders taller than she, and not only is he too heavy for her to lift even at his much-diminished weight, but my grandfather had been suffering from an infection that left ugly, black sores on his foot. The infection made his already shuffling steps more labored, and his balance even worse. So my grandmother called me in to help.

I can’t do much. I’m only slightly taller than my grandmother, and the two of us together can’t support his dead weight. After many minutes of struggling we manage to get him as far as sitting at the edge of the bed, and my grandmother tries to feed him his breakfast there, which is another ordeal as my grandfather, who once had a voracious appetite, refuses to eat these days. Every time he spits out the cereal my grandmother spoons into his mouth I can see her frustration mounting, and then the doorbell rings. It’s the aide whom my grandmother asked not to come back, explaining that the train made her late. I tell her I understand how the trains are, but my grandfather needs to get up.

The aide speaks with a heavy Haitian accent. My grandfather, who is irritated by any language that isn’t his native Italian, doesn’t understand her and doesn’t like her. He tells her to leave and curses at her, but she doesn’t seem to understand him and smiles. She lays a comforting hand on his arm, and he shouts, “Non mi toccare!” Don’t touch me! That she understands, but she’s the only one who is capable of getting him into the kitchen and bathroom.

My grandmother tells me I can leave now that the aide is here. She looks very weary as I walk out the door, and it’s only the beginning of the day.

My grandfather, like an estimated 5.3 million people in the United States, has dementia. By 2050, that number is expected to go up to anywhere from 11 to 16 million people affected by this disease, according to Walter Ochoa, director of the Brooklyn facility of the international in-home care organization Right at Home. This is not an epidemic, Ochoa tells me, but instead a consequence of longer lifespans due to the miracle of modern medicine. A person’s chance of developing dementia increases after the age of 65 and peaks around the mid-70s. As of now, there are about 35 million people in the United States aged 65 and older; that number is projected to more than double by 2030. It’s a phenomenon that Ochoa refers to as the “silver tsunami”: the Baby Boomers are becoming senior citizens, and with that come the issues of old age, like dementia.

Specifically, my grandfather has vascular dementia; that is, mental deterioration caused by a series of strokes that deprive the brain of oxygen. Vascular dementia is the second most common form of dementia after Alzheimer’s disease, which is caused by a buildup of proteins in the brain that block the communication of neurons. The end result, however, is the same: parts of the brain begin to waste away. It starts at the hippocampus, which is located in the middle of the temporal lobe and stores short-term memory, and temporal lobe, which aides in understanding language. Then it moves on to the frontal lobe, which manages problem solving and decision-making. Then, on to the parietal lobe, which manages sensory information; manifestations of these symptoms would constitute a moderate case of dementia. The most severe stage comes when the occipital lobe, which manages long-term memory, is affected. A person with dementia can live for many years with this slow deterioration, even as long as a decade. At the end, a person who dies with dementia has a brain weighing one-third that of a healthy brain.

There’s no cure, and there’s no reversing it, and the unfortunate fact is that we, my family, didn’t recognize the signs that something was terribly amiss with my grandfather until it was too late.

The symptoms were small at first. He began to walk with an odd shuffle, head bowed so far forward it looked like he would fall. He would ramble about an old love affair nobody could be sure was true, saying that he had to find her. He would take up obsessions and forget them just as fast: collecting coins, playing the lottery, wanting to speak to the president of Italy. We thought he was senile, or depressed, or maybe his hearing condition was causing the confusion in his head that he complained of so often. But taking my grandfather, who firmly believed doctors were a waste of time and money, to be tested was no easy task. He would go to his primary care physician for rounds of scans and blood tests, never to follow up. If he would be prescribed pills for his blood pressure or diabetes, he would take the pill every other day instead of every day to make them last longer so he wouldn’t have to pay for a refill. That’s just how he was, and that’s how his three daughters – my aunts and my mother – let him be.

Around 2009, he saw a neurologist affiliated with his general practitioner, who saw in an MRI that my grandfather had suffered from mini-strokes. The neurologist prescribed him Aricept, a pill designed to treat the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease, though he never officially diagnosed my grandfather with any form of dementia. Even on the medication, his confusion only got worse. It would take him a half hour to walk a few blocks; this irritated my grandmother, who was convinced he was just dallying. Whenever my grandfather would see his doctor, it seemed he would only come home with another prescription, a higher dosage, a recommendation to come back in six months, but no answers as to what was wrong with him. My mother went along to see his neurologist and asked if her father should have another MRI and compare the scans, but the doctor said that would not be necessary and increased the dosage of Aricept. She recalls the frustration of not understanding why nothing could be done.

“They weren’t being clear with us,” she said. “If they knew it was dementia, they didn’t verbally say that to us.”

Unfortunately, this is not an uncommon occurrence for people suffering from some form of dementia. According to the Alzheimer’s Association, only 45 percent of people with Alzheimer’s disease or their caregivers reported being told of their diagnosis.

In 2012 my mother took him to a cardiologist, also affiliated with his general practitioner, who said he had hardening in his arteries and needed a valve fixed. The procedure was simple, but because of his age, the cardiologist recommended he spend the night in the hospital. My grandfather decided then that he didn’t need his valve fixed.

Also in 2012, my grandparents went to Italy for the last time with their eldest daughter, my Aunt Amelia. On the flight to Rome, my grandfather demanded that the stewardess let him in the cockpit to see the pilot, since he was allowed to once in 1971.

After that trip, he went back to the doctor. In 2013 he saw a different cardiologist, and once again the doctor recommended surgery to fix the arteries that were blocking oxygen from his brain. The first operation to put in a stent went very well; so well, the doctor thought my grandfather would be able to endure multiple stents in the next operation. The next operation went horribly. Blood began to pool around the lining of his heart. His organs began to fail, and he was put on dialysis. What was meant to be an overnight procedure turned into a weeklong hospital stay. He was very weak at this time, so weak we couldn’t be sure if he would make it. But as his body recovered, it was clear that his mental state had declined.

A list of the standard symptoms of dementia, provided by In the Know Certified Nursing Assistance, reads like a checklist of my grandfather’s life these past two years. Showing poor judgment and making poor decisions – as when he asked a complete stranger to help him run away and was stranded at the corner, check. Getting lost in familiar surroundings – as when he went to buy lottery tickets in the neighborhood he’s lived in for 40 years and couldn’t find his way home for two hours, check. Seeing or hearing things that are not there – like the “friend” in his head who tells him he should be a saint, check. Losing his ability to understand or use speech – like when he tells me he loves me but could I please stop talking because he can’t understand English, check.

And then there are the symptoms that have become life’s daily battles: neglecting personal hygiene, utter refusal to eat, becoming restless at night when my grandmother is trying to sleep, wetting the bed, behaving inappropriately, becoming aggressive. My grandmother remained his primary caregiver throughout all of it.

After his surgery, the city appointed him a nurse through the Visiting Nurse Services of New York. She came with her own health issues; she was in her sixties, nearly as old as my grandmother, and said she wouldn’t be able to lift my grandfather on her own. That meant my grandmother would have to help the nurse with the tasks she was being paid to do, in particular helping with bathing and dressing.

That same year, my Aunt Amelia took my grandfather to see a different neurologist. He sent him for a brain scan, and as they waited for the results, he talked to my grandfather. He asked questions about dates and names, from years ago to more recent events. My aunt says my grandfather got many things wrong. The doctor then showed them the brain scan on his laptop. He pointed to the large white areas that indicated the parts of his brain that were, literally, lost.

These damaged areas, the doctor explained, were caused by a series of mini-strokes. No one was aware of these strokes because he was not being monitored by a doctor. My grandfather was formally diagnosed with vascular dementia, the reason for his memory loss, his lack of bathroom control, his nasty attitude. It was the latter symptom that prompted the neurologist to prescribe him a medicine to calm him down, a pill that needed an increased dosage after just three months.

With this diagnosis, we, as a family, had to face some harsh realities: He was not going to get better. He was undoubtedly going to get worse. There was the fear, particularly for my aunt and my mother, that they might be looking at a similar future. And then the guilt. How did we not notice he was in distress? How did the glazed look, the confusion, the excessive salivation, go unquestioned? Why did we assume this was what old age looked like? And then the worry – not for him, whose fate was, in a word, sealed, but for my grandmother. How could she deal with the daily bathing and dressing, the nightly bed-wetting, and the constant complaints?

Ochoa tells me that 75 percent of caregivers for patients with dementia are family members, which clearly puts massive stress on a person who is dealing with the illness of a loved one while also learning how to deal with that illness, likely on his or her own. He mentions a study that a doctor conducted on dementia patients to see how many died within a five-year period. The doctor found that none of his patients died, but five family members did from stress-related diseases.

My grandmother was already showing signs of strain. She had no patience for the feeble, cantankerous man who replaced her husband of 54 years. And, as if this disease was not content to take just one of my grandparents, she seemed to age a decade overnight, her face worn with exhaustion and her back hunched with the effort of taking care of her husband. She needed help, the kind that none of us in the family could give. My Aunt Amelia lives in Westchester; my family lives just two blocks away from my grandparents but my mother works full time, and my Aunt Daniela, 13 and 10 years younger than her sisters respectively, has three young children. Ochoa would call my family part of the “Sandwich Generation,” children of a generation living longer than ever before. Fifty years ago, when the average lifespan was around age 70, people didn’t need to care for the elderly parents as they do now. The Alzheimer’s Association has found that “sandwich generation caregivers indicate lower quality of life and diminished health behaviors (for example, less likely to choose foods based on health values; less likely to use seat belts; less likely to exercise) compared with non-sandwich generation caregivers.” Neglecting one’s health is especially dangerous if one has a predisposition to vascular dementia, in which ill health could lead to a stroke.

“People are dying in their 80s and 90s, and now you need to take care of your kids and your parents,” Ochoa said. “You have to take your kids to soccer and to ballet, and then your father calls to say ‘I need to go to the hospital.’ It’s very stressful for that generation.”

Statistics from the Alzheimer’s Association roundly support that claim: its studies found that 59 percent of family caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s and other dementias rated the emotional stress of caregiving as high or very high. Additionally, approximately 40 percent of family caregivers of people with dementia suffer from depression, which increases with the severity of the disease.

Facing this, my family decided to find another nurse. It was at this time that the complicated, confusing and oftentimes convoluted insurance laws began to rear their ugly heads. As people over the age of 65, both my grandparents were eligible to be covered by Medicare as their insurance. Medicare paid for the nurse from the Visiting Nurse Service of New York, and also for physical therapy that the cardiologist recommended. However, the Visiting Nurse Service required that its own professionals administer the physical therapy, not the physical therapist office located very close to my grandparents’ house. The Visiting Nurse Service did not respond to calls for comment about that rule.

My grandmother decided she would prefer a private home assistance service. My Aunt Daniela found one in the church bulletin that advertised Italian-speaking aides. The service is called Right at Home, and it is the one we are using still. My grandfather’s current aide is the third one he has had through this agency; her name is Hafida Bologna, and right now she’s a good fit. She speaks Italian very well, and was well taught by Right at Home services how to feed, wash and even change diapers, give medications and take the blood pressure of her ailing clients. But more importantly, she has an innate ability to have patience, to soothe his agitations and make him feel safe. She prays with him, something not taught by Right at Home but which seems to work well. She tells me she takes care of my grandfather as she would her father. It’s a relief for my aunts and my mother that there is a trustworthy person to help both my grandparents, but the situation is still not ideal.

That’s because, at this point in time, the nursing service is being paid out of pocket, and at $19 per hour, that’s $912 monthly for the aide who comes only three days a week, four hours at a time. But my grandfather has dementia every day of the week, not just Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays. A full time aide would cost in the range of $5,000 per month, which is more than my grandparents earn. They have to pay because like most home care facilities, Right at Home does not accept Medicare. According to the Alzheimer’s Association, Medicaid is the only public program that provides long-term care coverage, but beneficiaries must be low-income individuals; to be eligible for Medicaid for the purpose of home care assistance, a single person has to make less than $825 a month, and own less than $14,850 in assets. Most people deplete their income and assets paying out of pocket for services like nursing homes and assisted living, the Alzheimer’s Association found.

My grandparents came to the United States as immigrants in the 1960s. My grandfather owned his own barbershop and worked for 45 years, until he was 75 years old. My grandmother was a seamstress, working in a factory until she had children, and then working from her basement. They paid into Social Security, but because they worked for themselves, the checks they receive now are modest. They lived their version of the American dream by buying property, a four-family apartment building in Bensonhurst, and most of their income came from the rent they collected. My grandfather also receives a small pension from Italy for the time he served in the carabinieri, the Italian police force. The didn’t have much, but they saved for their old age, so that they wouldn’t find themselves with nothing. Now, to be eligible for Medicaid, they have had to forfeit it all.

My aunts and my mother found other legal channels through which my grandfather would become eligible for Medicaid. Instead of letting my grandparents funnel all their money into caring for his disease and selling their property, they contacted a lawyer to guide them in moving all assets into their name. This process actually began six years ago, when my grandparents and their daughters began planning for their estate should one of them fall ill. Knowing from the experience of friends and family members that Medicaid should be an option, they drew up, with the help of attorney (now Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce President) Carlo Scissura, an irrevocable living trust. With that document, all the assets that belonged to my grandparents – the building, a few savings accounts – now belong to my aunts and mother equally. Though the trust has been effective for years, it’s a different feeling in the family now that it’s a necessity. It feels as though everything my grandparents worked for in their lives amounted to nothing.

There’s also dissatisfaction about how this system works against people who fall firmly in the middle class. My grandparents don’t have the money to afford the level of care my grandfather needs, but they have too much to qualify for programs like Medicaid without changing their lives. As my mother Patricia said, “You either have to be filthy rich or dirt poor.” My Aunt Amelia echoed the sentiment: “It makes you feel that unless you’re very wealthy or very poor, you have to struggle.”

More recently, they were granted power of attorney, this time with the help of eldercare lawyer Ida Como from the firm of Silvagni and Como, giving them the authority to make decisions on behalf of their parents. Como also prepared the Medicaid application for them; all they had to do was provide the necessary documents, such as identification, utility bills and proof of income. But this convenience doesn’t come cheap: the Medicaid application plus the power of attorney document cost $4,500.

A lawyer is not a necessary requirement. The Medicaid application is available to everyone to apply to for free. But the many rules and regulations of the process are intimidating, and an error based on ignorance of the system would mean a denial of the application. Should the request be rejected, the whole application process would need to begin anew, or the other option would be to appeal and request a hearing before an administrative board, according to Como. This doesn’t sound too devastating, until you think about what precisely it is that has been rejected. Every day without the means to afford home care assistance is another day of struggle for my grandfather, every week is another hefty sum gone, and every month of waiting for the application to be reprocessed is time that his condition is worsening without the proper care.

Of course, just because a lawyer submits the application doesn’t mean it will be approved. “There are no guarantees,” said Como. “Only that the attorney knows what Medicaid will be looking for.”

At this point, my grandfather’s Medicaid status is pending. Although my aunts and mother started the process this past autumn, and three months is the usual amount of time it takes to take care of all the requirements, there were some issues that caused roadblocks; for example, the application required a letter from the Italian government to prove how much he receives from his pension, because the direct deposit was not “acceptable.” Waiting on the Italian government is a situation no one wants to be in. But the obstacle was surmounted; now all there is to do is wait.

Meanwhile, that foot that was causing my grandfather problems months ago is flaring up again. Those ugly black sores just won’t go away. He had been getting stronger, but now he’s having trouble walking again. More worry, more doctors’ visits, more bad days; the unrelenting cycle of what it means to have dementia.

We deal with each issue as it arises, and who knows what’s coming at us next.

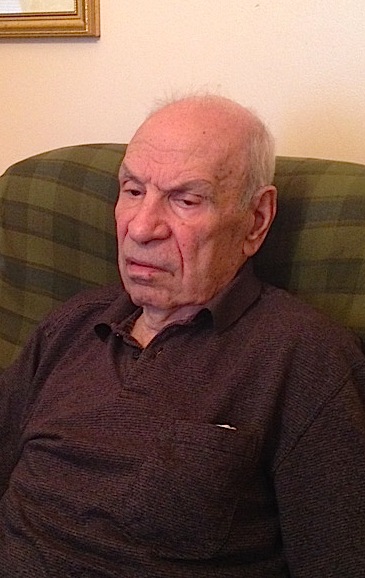

Photo, top: Carmine Angotti served as a member of the carabinieri as a young man in Italy.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.