By KRYSTAL DANIEL

As he leans back in a white mesh-back office chair with one foot chucked on top of his cluttered desk, it’s hard to believe Anthony Papa, 56, was locked up in a “6 by 9 cage” at Sing Sing maximum security prison for 12 years of his life under the Rockefeller drug laws.

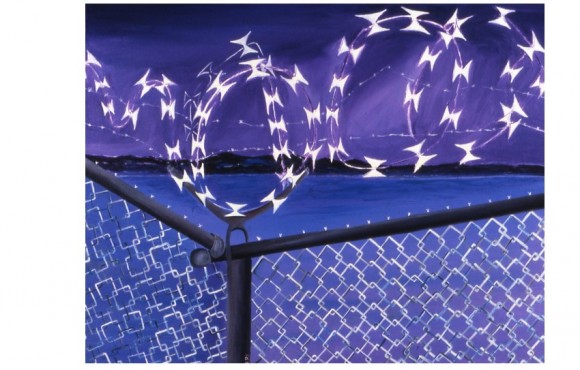

“It was a living nightmare,” Papa said with a deep sigh. “There was daily stabbings and fights. It was just a horrible place to be. Being inside if you weren’t a bad person, you would become one.”

Aside from the violence, Papa recalls the battleship grey interior of his small cell, sleeping on an uncomfortably thin cot with springs sticking out, and a tiny steel toilet bowl that doubled as a refrigerator.

In the midst of such deprived conditions, what was surprisingly most difficult for Papa was the constant sound of bells.

“Bells woke you up, bells put you to sleep, and bells told you when to eat. You had ten minutes to get your food and eat your food until another bell told you to get out,” he said. “I still have the habit of choking down food today.”

Sitting up and firmly planting his feet on the floor, Papa roused from the memories. The décor of his office space defines his most recent memories. Family photos scattered across the one side of the wall, while self-portraits adorned the other side. Sprinkled in-between were blaring red posters, contrasting the dark-grey, patchwork carpet. The posters read “Legalize Pot,” and “Support Medical Marijuana in New York.” Papa is the media relations manager for the Drug Policy Alliance of New York, where he advocates each day to further reform drug legislation.

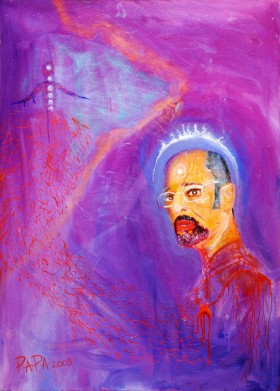

Papa, unlike most, was able to transform his prison stay into an artistically and educationally cultivating period of his life. Papa earned three degrees while in prison and discovered his passion for art, air jordan 13 femmes which led him on a path to freedom. Papa’s portraits were displayed in the Whitney Museum and after serving 12 years of a 15 year-to-life sentence, Papa was granted clemency by then-Gov. George Pataki.

Now on the other side of the spectrum, Papa and the Drug Policy Alliance strive to encourage New York State to take a less punitive approach toward drug users and peddlers. The state began moving in this direction when the Legislature agreed in 2004 and 2009 to change the draconian Rockefeller drug laws. Passed in 1973 under Gov. Nelson Rockefeller, these laws had mandated minimum sentences of 15 years to life for possession of four ounces of narcotics. The reform bill of 2009 shifted drug policy from a system that imprisoned offenders for extensive periods of time to one that generally imposes shorter sentences. But, at the same time, police are making narcotics arrests at historically high rates, continuing what Papa and others say is over-reliance on punishment rather than a needed focus on treatment and prevention. A growing system of drug courts in New York State has shown that creating alternatives to incarceration does indeed work well to prevent recidivism. But only a small percentage of narcotics cases goes through them.

* * *

The New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services issued a report in 2012 showing that the number of felony drug arrests of adults in New York City has dropped gradually since peaking for the decade in 2007, but that misdemeanor drug arrests have been on the rise, a reduction of about 500 between 2010 and 2011. In 2002 the total amount of misdemeanor arrest was 189,718, it peaked in 2011 at 249,211.

The rising numbers of misdemeanor drug arrests in relation to the shrinking number of felony drug arrests indicate a heightened police effort and a policy shift which experts say isn’t necessarily combating the drug issue.

“Historically, the rise and fall of drug use in society has not had a direct relationship to law enforcement practices,” said Naomi Braine, a sociology professor at Brooklyn College.

It is a grave misconception that heavy policing combats drug problems, experts say. “There seems to be an unlimited infinite elasticity in young people willing to use and sell drugs. Neither of those behaviors is influenced by the threat of punishment,” said Alex Vitale, criminologist and sociology professor at Brooklyn College.

Historical data reveals the unsuccessful results of punitive measures towards drug use. Under the Rockefeller drug laws, judges at first were required to impose a minimum sentence of 15-years-to-life for anyone convicted of selling two ounces, or possessing four ounces of narcotic drugs such as cocaine, heroin, morphine, opium, and cannabis. In 1977 cannabis possession that was less than 7/8 of an ounce by weight was removed from the list of offenses covered under the Rockefeller drug laws because of a fear of exhausting criminal justice resources for marijuana offenders. Shortly after, in 1979, the Legislature responded to widespread criticism by changing the laws to require a larger amount of drugs possessed or sold to impose the 15-year to life sentence. In 1988, during the crack epidemic, the Legislature lowered the weight threshold for crack-cocaine, enabling prosecutors to obtain harsher sentences for smaller amounts of the drug.

In 1985, Papa, then 29, was broke and barely scraping by; he was self-employed and operated his own radio and alarm installation business. “I was part of a bowling league in Yonkers,” said Papa. “I was always late to the games so one day a team member asked why I kept coming late.” Papa was often late to his games because his car kept breaking down and he had no extra money to fix it, which made his teammate’s offer even more enticing.

“He asked me if I wanted to make some extra money and I said yeah,” Papa recalled. Papa was given a small envelope to deliver and compensated with $500, not much compared to the cost of losing his family and 12 years of his life. The envelope contained four and a half ounces of powder cocaine, air jordan spizike enough to fill the empty box from a deck of playing cards.

“As soon as I handed the envelope over to this guy about 20 cops came out of nowhere,” Papa said, jolting up in his office chair as if it happened yesterday. “I kept my mouth shut and ended up with a 15-year-to-life sentence.”

Papa, who is Puerto Rican, was among the thousands of young minorities cast out of society and thrown in cages for decades at a time under the Rockefeller drug laws. In 2009 the Drug Policy Alliance reported that most of the people incarcerated under the Rockefeller laws were convicted of low-level, non-violent drug offenses and most have no prior criminal history.

In 2009 about 12,000 people were locked up for drug-related crimes and two years prior, 6,148 people were imprisoned; 94 percent of the convictions were for the for category B, C, D, and E felonies which usually do not include fatal violence.

With heaps of conclusive data, past and present, confirming the constant malfunction of drug legislation, one question comes to mind.

Why?

Historians say that drug policy, past and present, is largely a result of political reactions to the public attitude. Among the first drug laws passed was the Harrison Act of 1914, the first attempt at regulating the distribution of opiates. At the time, vast numbers of Chinese people immigrated to the West Coast to work as laborers on the expanding railroad network. The Chinese brought with them the habit of smoking opium rather than injecting or drinking it, as many Americans of the middle and upper classes did at the time. Smoking opium became generally frowned upon because of its association with immigrants but drinking and injecting it was acceptable considering the “good people” (white, upper class people) did it.

Fast forward to the implementation of the 1973 Rockefeller drug laws and the same pattern of implementing regulations to coincide with public attitude is evident. “The politics of this initiative were driven in part by then-governor Nelson Rockefeller’s aspiration for national office,” said a paper published in 2009 by the New York Civil Liberties Union. “Any such candidate must demonstrate a commitment to upholding law and order.”

In the early 1970’s there was a drastic increase in heroin use and property crime, which the public viewed as a growing safety threat from addicts and pushers. Rockefeller responded with “tough on crime” legislation.

As a result, in 1974, 200,000 people were sent to prison for drug offenses, a number that sharply increased in the 1980s and recently began to creep down.

In April 2009, then-Gov. David Paterson took the first hefty step toward remedying decades of inept drug laws by signing legislation that enacted real reforms. He eliminated mandatory prison sentences for most drug offenses, expanded probation and other alternatives to incarceration, and provided retroactive resentencing for about 1,200 people incarcerated under the old laws.

“My friend Amir was sentenced to 25 years-to-life for a non-violent drug offense under the Rockefeller drug laws and ended up doing 19 years of his time,” Papa said. While in prison, “he was busted for smoking a joint and his merit time was taken away. This made him ineligible for judicial relief under the 2004 reforms.” Once Amir was reprimanded for breaking prison rules his application for judicial relief was automatically banned from consideration by a judge.

In 2009 Amir was finally released. “That was a $250,000 joint,” Papa said with a grin. The additional five years Amir spent in prison cost taxpayers roughly $250,000, or about $50,000 per year. The NYCLU classifies lengthy prison terms for non-violent drug offenders as an “exorbitant waste of tax dollars.” The NYCLU reported that New York’s annual expenditure for incarcerating drug offenders is more than half a billion dollars.

The cost of treatment programs, on the other hand, is significantly less. The cost of residential treatment is $30,700 per year and $13,900 annually for outpatient treatment. The adoption of policies that promote treatment and rehabilitation can save taxpayers between 39 and 72 percent of the cost of incarceration, the NYCLU reports.

“A public health approach is the only effective way to respond to drug use. A good public health system has to be implemented, it will have to be universal coverage so people could get the help they need when they need it,” Braine, the sociologist, said. “Better access to healthcare and more community programs would allow people with drug problems to see a doctor more regularly making them less likely to end up in really bad shape.”

In tune with a less punitive approach New York State has implemented 161 drug courts. They work to put drug-addicted persons in treatment programs as an alternative to prison. In a collaborative effort with defense attorneys, prosecutors, treatment and education providers, non-violent addicted offenders become part of an intervention process with the ultimate goal of keeping them clean.

“Study after study has been done on drug courts in New York and it’s no question in anyone’s mind that they are not effective. Recidivism rates of people referred to the drug courts are low,” said David Bookstaver, communications director for the New York State courts.

Although not all drug offenders are eligible for treatment programs, the drug courts do reach a percentage of them. In 2009, the New York State Unified Court System reported 4,969 eligible participants in New York City; 2,968 refused participation. That is a relatively small percentage of the 108,689 persons arrested for felony and misdemeanor drug offenses in New York City that same year, adidas neo as reported by New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services. While progressing slowly, New York in headed in the direction of a less punitive approach.

The Obama administration’s National Drug Control Strategy has also sought to break the cycle of drug use, drug-related crime, delinquency and incarceration. The government has taken steps to provide communities with the capacity to prevent drug-related crime by arranging services that improve community-police relations. The administration also supports drug courts as an alternative to incarceration.

According to the National Association of Drug Court Professionals, there are over 2,600 operating throughout the nation. Most importantly the Department of Justice provides grant funding through the Second Chance Act, legislation designed to improve the outcome of people reentering society after release from prison.

The goals of the federal government to transform drug policy into a health- oriented system are consistent with the objectives of advocacy groups and experts who disapprove of a punitive approach. But they say that the shift in New York State spurred by the 2009 reforms has yet to live up to the federal approach, even though steps are being taken to get there.

Nevertheless the constant increase of misdemeanor drug arrest reveals a sharp contrast in state and federal policy.

Even with the federal government’s efforts to apply a public health approach to drug policy, more may need to be done on the local level. “A jobs program for poor communities should be provided. A lot of people selling drugs don’t have a drug problem, they have a jobs problem,” said Vitale, a criminologist. “Drugs should be legalized and decriminalized. “The sale of drugs can be regulated much like alcohol and tobacco are.”

The complete legalization of drugs is improbable for now, but creating alternatives to prison and releasing people from its many horrors is a bountiful step in the eyes of many.

Papa recalls eating a steak dinner on his first day out of Sing Sing. “I freaked out when I held a glass in my hand. It was like a Zen experience to feel an object I hadn’t felt in years,” he said. “When I drove through my old neighborhood everything looked small and out of proportion. My sense of feeling, sight and smell took a while to adjust. Civilian clothes didn’t even fit right.”

Papa continued with his arms crossed on his chest, the scar across his forehead expanded as and a look of deep concentration took over his face, “It was like being born again.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.