By DEREK NORMAN

Residents of East Harlem are taking what they say are defensive actions to prepare for the Trump administration’s anticipated policies on immigration, with protests, forums and arranging legal counsel.

“El Barrio,” or Spanish Harlem, is a neighborhood of about 126,300 residents, with a Hispanic population of about 55 percent. About 1 in 5 residents are documented immigrants, and many more, especially a large number from Mexico, are undocumented. Donald Trump’s victory in the presidential race has clearly unsettled the community.

“It’s almost like after a hurricane when you first check your loved ones, then look around to see all the destruction and you begin to realize how many people were affected,” said Jessica Sabia, director of college counseling at the Young Women’s Leadership School of East Harlem, an all-girls high school on 106th Street. “There’s been a lot of uneasiness and uncertainty. I think a lot of people were preparing for this, but still a lot of people at the school and in our community, including myself, just kind of assumed that this would never happen. Maybe I was naïve, but I wasn’t prepared.”

During his campaign, Trump advocated deporting millions of illegal immigrants, building a wall on the border of Mexico, revoking an executive order in which President Barack Obama deferred deportation of immigrants who entered the country illegally as children and overhauling immigration law. All of this would have a direct effect on many residents of East Harlem.

Non-profit organizations began community outreach almost immediately to assist undocumented immigrants in the community. The Legal Aid Society hosted a forum on Nov. 17 in the basement of St. Paul’s Church at 113 E. 117 St.; attendees were allowed to be anonymous. The group provided free legal counsel and information on current immigration law to residents, who had many questions.

“Nothing can change until Jan. 20, when he’s inaugurated. So even though he’s saying all these scary things, we have the time now to sort through our resources,” said Anthony Posada, an immigration attorney for the Legal Aid Society. “He was saying he’s going to deport 11 million people, and now he’s saying only two or three million, so we’re going to have to wait and see.”

One threat that is troubling residents of East Harlem is Trump’s plan to remove Obama’s Deferred Action upon Childhood Arrival policy, or DACA, which allows children who arrived under the age of 16 to work and attend school. It provides some protection against deportation.

“For people who have DACA now, and the people who have to reapply in the next six months, it’s okay to go ahead with the process, as the government already knows about you,” said Posada. “But if you don’t have it already, what we’re suggesting here at the Legal Aid, is that you should not apply. The government does not know about you and this is not a safe time to bring yourself to their attention.”

DACA and Temporary Protected Status, which permits exceptions on a humanitarian basis for emigrants of certain troubled countries, are the only immigration policies that Trump can remove by executive order; anything else needs to be approved by Congress.

Many immigrants in East Harlem who were not qualified for DACA said that they have been speaking with attorneys for advice. Their attorneys suggested they deliberately put themselves into the deportation process, to argue their case in front of a judge, which, according to the Legal Aid Society attorneys, is a “terrible idea.”

Many residents are complaining that they cannot trust attorneys because some are trying to take advantage of the circumstances, by accepting money for legal assistance, knowing that the client will not make progress. As one woman said, several “notarios” have already approached her.

Notarios is the phrase given to notaries public Latin America, more formally, notario publicos. But, as opposed to the United States, in most Latin American countries, notary publics are the equivalent of a person who has received a license to practice law. Lost in that translation is the opportunity for individuals to hustle immigrants into paying for false advice and incorrect forms.

“I know there’s a lot of notarios out there saying ‘if you pay me $10,000, I’ll get you that 10-year-thing,’” Posada warned those in attendance. “But it’s not that easy. If you pay that money to the notario, when it comes time for deportation, they’re not going to be able to help you because you have no defense.”

“One thing we’ve seen a lot is when people are approached in the street by police, is that there don’t have legal reason to call someone over to them,” said Posada. “But people fail to produce identification, and that could lead to being detained until the person can be identified. So the main thing we are trying to get people to understand is that they need to carry an ID with them at all times. They are afraid of being identified, but it could actually save them.”

While attendees at Legal Aid Society forum were middle-aged, younger members of the community were also looking to take initiative.

“I know there is one teacher [at the Young Women’s Leadership School] that is trying to encourage love and peace, which is not the stance of some other teachers. So we aren’t building a generation that is just so angry,” Sabia said. “I want to work with these students to help them understand their immigration status and what they can do. A lot of things they can’t be confident about, but at least they’ll be educated and can tell their families. Because I think a lot of families just don’t know what to right now.”

The teacher referred to had her students cut out paper hearts, which she intended to hand out in front of Trump Tower the next weekend.

“When we first heard about it, I didn’t react as much as others. Some of my friends were coming up to me asking, ‘so, are you ready to go back?’ and didn’t really bother me,” said a 17-year-old student at the Young Women’s Leadership School, an undocumented immigrant from Mexico. “It’s going to affect me because I wasn’t born here, but we were kind of taking it as a joke. I know we shouldn’t because a lot of people really are going to be sent back. Everybody at school started talking about it and then when I started to see people crying, I started crying too.”

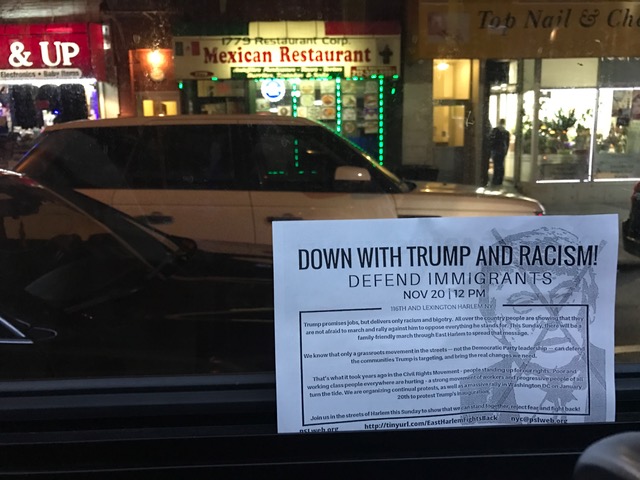

One anti-Trump protest march took place on Sunday, Nov. 18, led by an activist group called the ANSWER Coalition. A handful of people congregated on the corner of 116th Street and Lexington Avenue before marching with their signs to the South Bronx.

The protesters, mainly young whites who described themselves as socialists, carried signs and banners saying that the group “stood by immigrants” and was there to defend them.

“I appreciate what they are trying to do here, but it’s Sunday. A lot of people are just getting out of church, some have to go to work, and we just can’t put ourselves out there like that,” said one East Harlem resident who refused to give his name.

A lot of immigrant residents feel they can’t demonstrate in public or resist, as they are more vulnerable to consequences because of their immigration status. But many expressed a sense of unity as resources and supportive conversations were organized in the community of East Harlem.

“This means that we just need to work harder than before. The day the results came, my teachers had talks about what could happen and I started crying,” said a 17-year-old student at the Young Women’s Leadership School who is an undocumented immigrant from Mexico. “I started crying not because of the results, but because my community was coming together in support and that is going to make us stronger.”

Photos and video by Derek Norman.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.