By ENRICO DENARD

For people whose ancestry has been painfully intertwined with slave history, constructing a family tree can be a difficult topic. As part of Black History Month, genealogist Phillip Nicholas mapped out the steps to discovering family at a Feb. 9th virtual presentation for the Yonkers Public Library.

Especially for people of West Indian descent looking to track distant relatives, Nicholas said, it’s a good idea to expect the unexpected. “What you assume about your family history might be not what happened,” he said.

How can you get started? Simply by talking to your family, Nicholas explained. You will need to gather as much information on your lineage in family names, addresses, and health records as possible. While it may be heartwarming to catch up with mom and dad or that distant cousin who stole your T-shirt, the information scientist warned family genealogists to weed out the accurate details from what your family has assumed.

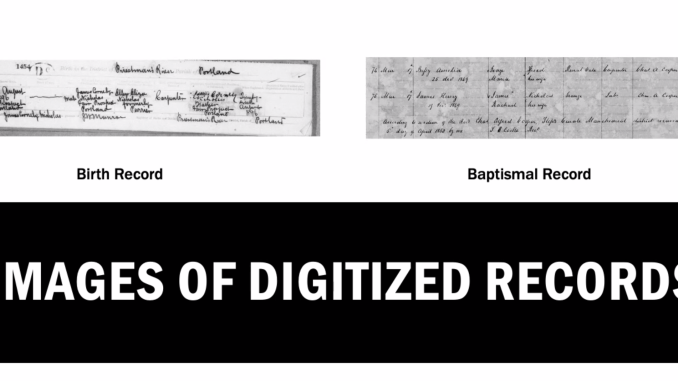

You may find a jumbled mess of birth certificates, occupational, health, and death records awaiting, depending on how deep you choose to dig. Nicholas showed a shortlist of blurred family records that are centuries old. However, a good chunk of immigration documentation should narrow the search. “Knowing when your family group migrated from the West Indies is important to know,” he says.

Nicholas’ heritage is proof that the unexpected should be expected. In tracing his immigrant roots, which in his case consisted of Jamaican and British ancestors who were masons and carpenters, he discovered his family history was not directly affected by the slavery in Jamaica.

After months of piecing together his families’ immigration and occupational history, Nicholas disclosed, “My four-times-great grand grandfather was a well-established and literate community member of Jamaica, although he was still young at the time slavery had been abolished.” If one thing is certain about unpacking West Indian ancestry, you never know what you might find.

Nicholas, a former Maryland University student of library and information science, said the process of finding those records can be addictive. Salve owners loosely managed records of their slaves, but before the abolishment of slavery in British territories in1834, so-called “marshal sales,” or the slave-trading marketplaces, reflected an expansive cultural community.

West Africans migrated to Jamaica from Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire, and Mali. In Jamaica there was also a strong presence of European people of German, Portuguese and French descent, and a farrago of East Asian, Middle Eastern and Native people, all networked in British slave trading. Nicholas reassured listeners that genealogy companies are working to identify all the elements in this expansive pool

“Even while you look for this information, findmypast.com and ancestry.com are updating naturalization records steadily,” he said. However, “It can be costly and take up to two years to retrieve the information.”

One last step you can take to connect the dots, the ancestry researcher said, is to take a trip to Jamaica. The United Nations, Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) has archival libraries in Kingston, Jamaica, that include slavery documentations under the British rule until reparations were made to the enslaved in 1838.

You do not have to be a citizen of Jamaica to use the records. Nicholas said it may be worth the trip to piece together West Indian history, as the country was once a hub for slave activity and now hosts the UNESCO Slave Route Project that has a site you can visit near the Blue and John Crow Mountains National Park about one-hour’s drive from Kingston.

Source: https://slaveryandremembrance.org/