By MARCO POGGIO

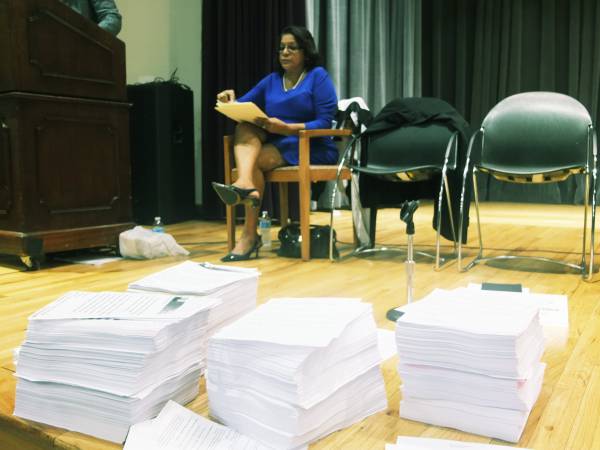

It had rained unceasingly for a few hours, but that did not prevent more than 400 residents from showing up in the basement of John Hus Moravian Church on Ocean Avenue last April.

The town hall meeting was convened to discuss a 23-story luxury tower that was going to rise at 626 Flatbush Ave., on the edge of Prospect Park. In the weeks previous to the meeting, word had been going around in the community that the development would cause more harm than good.

The meeting began with a prayer, as often happens. But grace and silence did not last long. People anxious about displacement lined up at the microphone in search for answers.

“We are fearful, we are just asking for help,” said Natasha Worden, whose family has lived along Flatbush Avenue for nearly 50 years.

“I’m asking for the same treatment Mayor de Blasio’s neighborhood gets!” said Quest Fanning, 35, who has lived all his life in the neighborhood.

“What can the borough president’s office do to stop the building or at least reduce the height?” asked Carl Blake, who said he owns a toy store nearby.

Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams was there to respond: his priority was to boost housing development, not oppose it.

“We have a housing problem in the city, and Brooklyn is at the heart of that housing problem,” Adams said. “I don’t sleep well at night when I go home to a warm house every night and other Brooklynites don’t do that.”

Whoever came to find comfort in the words of the borough president ended up disappointed. But to many in the audience that night, his pledge to fight for affordable housing sounded sincere.

In the months that followed, however, things would change drastically.

During the summer, a fierce anti-gentrification sentiment set in among the residents who live in the blocks south and east of Prospect Park and the Brooklyn Botanical Gardens, prodded by the fear that new luxury developments will lead to higher rents that force them out of the neighborhood.

That fear was underscored by the displacement trend they have seen in nearby Bedford-Stuyvesant and many other Brooklyn neighborhoods.

A problem began to arise for politicians like Adams, who like most of the city’s elected officials receives a big chunk of his campaign donations from the real estate industry. Constituents started viewing with skepticism the extent to which their elected officials were willing to protect low-income communities from the forces of gentrification. Grassroots movements found their footing in the public arena, and they are questioning the legitimacy of the politicians who were supposed to represent them.

“I think that the rage of some of the residents is definitely justified,” said Jerome Krase, a professor emeritus of sociology at Brooklyn College. “But they don’t realize that most of the people they are complaining about, including Eric Adams, don’t really have much power over the zoning, variance, and general development process.”

According to Krase, author of the book “Ethnicity and Machine Politics,” the African-American community mistakenly believed that politicians of color would serve them just because they share the same racial background.

“Historically, it has been the expectation of members of ethnic groups that when their own members get into political office they will see their primary mission as helping out fellow ethnics,” Krase said. “This has never been the case.”

* * *

Community District 9, which takes in South Crown Heights, Prospect-Lefferts Gardens, and part of northern Flatbush, became a political battlefield. The fight over the tower at 626 Flatbush Ave., became the focus as a court battle went to state Supreme Court in Manhattan.

According to court documents, Hudson Companies received $72 million in state loans from the New York State Housing Finance Agency.

Prospect Park East Network, a collective of local activists based in Prospect-Lefferts Gardens, sued both Hudson Companies and New York State Housing Finance Agency, the former for failing to engage with the community while drafting the project and the latter for pouring out taxpayer money without compelling the developer to produce an environmental review that would consider population density and other questions.

“It is so urgent that we address this problem, before it is too late,” said Suki Cheong, a member of Prospect Park East Network. Cheong, 37, grew up in Washington Heights but moved to Prospect-Lefferts Gardens nearly three years ago because, she said, she was charmed by the friendliness of the people in the neighborhood and she loved walking in Prospect Park.

During the town hall meeting at John Hus Church, Cheong made a name for herself after leading a 40-minute presentation in which she explained in detail all the various issues connected with the luxury tower Hudson was building half a block away from Prospect Park. One of her PowerPoint slides was a map showing the population density across the borough.

Many people were caught by surprise by the discovery that their local community district was the most densely populated in Brooklyn. According to the 2010 U.S. census, Community District 9 has more than 66,500 people per square mile.

Prospect Park East Network argued that a new residential tower would not only increase density, but attract more development in the future.

It especially infuriated the residents that 626 Flatbush Ave. was a luxury tower. Very few tenants in Prospect-Lefferts Garden could afford to pay $1,875 for a studio, $2,200 for a one-bedroom or $2,800 for a two-bedroom, according to market price provided by the developer.

Hudson posted on its website that the building would follow the so-called “80/20 Program,” meaning that 20 percent of its 254 apartment units would be made affordable, rented to families with a combined income between $33,400 and $41,750 per year.

SIDEBAR: WHAT IS `AFFORDABLE’ HOUSING?

Last May, Justice Peter Moulton of State Supreme Court in Manhattan issued an order that temporarily stopped Hudson Companies from building the foundation of the tower until he determined whether the project needed a new environmental study to proceed. But in June, Moulton found that Hudson was legitimately building “as of right,” allowing the work to resume.

It was a major victory for developers in Brooklyn, clearing the way for Manhattan-scale development in the low-rise neighborhood near Prospect Park.

In May, The New York Times real estate section had published a story describing Prospect-Lefferts Gardens as “on the map” for developers. Ten new luxury projects, scattered in the area comprised between Empire Boulevard and Clarkson Avenue, were in the works; 626 Flatbush Ave. was only one of them.

“They let the cat out of the bag,” said Edward Snajdr, an anthropology professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice. He suggested that the attention of the media made the transformation of Prospect-Lefferts Garden likelier to happen than it already was.

Snajdr, who has studied in depth the Atlantic Yards redevelopment and its impact on low-income communities, became an expert in gentrification studies in Brooklyn in recent years. During his two-year study, Snajdr said, he had a chance to observe the entire process in which real estate developers acquire property at relatively low cost and then turn it into a billion dollar revenue machine.

“The big controversy becomes ‘how do they get their stake on the land,’” Snajdr said, referring to real estate firms.

“They often get public subsidies to help it, in the name of development, which is politically OK to a lot of residents, not necessarily who lives in the neighborhood,” Snajdr said. “But the people who live in the neighborhood and did not have voice in that process, they get upset.”

Hudson Companies received the “421a exemption,” a tax break reserved to developers who create multi-family residential buildings and satisfy certain requirements for affordable housing.

Shonna Trinch, who is a colleague of Snajdr at John Jay College, and took part in his study, said the rent gap existing between neighborhoods triggers gentrification. Trinch said gentrification itself is an increase of the value of the land.

“Undervalued property begins to accumulate value through new development and ‘desire to be there,’” Trinch said.

She used an example to illustrate how the process takes place: a person who wishes to move to Brooklyn, but cannot afford to live in an affluent neighborhood like Brooklyn Heights, might decide to move into Crown Heights, where she is wealthier than the average resident.

Once she moved into the new neighborhood, the various services in the area suddenly turn their eyes to the new more affluent customer.

“It all starts with commercial, with retail,” Trinch said. Restaurants, dry cleaners and supermarkets begin to cater to new crowds with lots of money to spend. Prices will gradually go up and those who lived in the neighborhood for years are cut out of the process, soon finding out they cannot afford living in their old neighborhoods anymore.

Trinch’s example is the kind of scenario the residents of Prospect-Lefferts Gardens feared would ultimately take over their community. They don’t want to be priced out of their homes.

“Rents will go up. Where will the people go?” said James Betts, a long-time Prospect-Lefferts Gardens resident. When he moved into the neighborhood with his family 25 years ago, Betts said, he was attracted by its diversity and its affordable housing stock. Now, he is among those who are concerned the affordability will die, ironically, with the coming of new development that claims to provide affordable units.

“Someone mentioned that if rents rise then perhaps more opportunities for rental will be available,” said Rachel Hannaford from South Brooklyn Legal Services, one of the attorneys who assisted Prospect Park East Network in the legal filings against Hudson Companies.

“As an attorney who is in housing court every day representing poor people who can’t afford to stay in Brooklyn neighborhoods, I can tell you that, when rents rise, people are evicted and become homeless. And that is what could happen here,” Hannaford said during the town hall meeting last April.

Having witnessed Hudson’s success in building “as of right” thanks, local residents began asking their elected officials to push for a rezoning of the entire area. Their aim is to avoid more high-rises.

* * *

At the beginning of the summer, the focus suddenly turned to another and even more attractive portion of Community District 9. A mile-long portion of Empire Boulevard stretching from Prospect Park to New York Avenue presented all the features that made it vulnerable to overdevelopment: land at low cost, ample lots, and a zoning that allowed tall buildings.

Alicia Boyd, a Sterling Street resident, began stirring up allegations that had Adams as at least partially responsible for using his power within the city’s land use process to invite development people did not want.

Boyd, 54, formed a tenant group she called Movement to Protect the People, which met every Tuesday. In August, Boyd and her group attended a meeting held by Community Board 9 that focused on the proposed study plan for a rezoning of part the community.

“The mayor’s plan talks about preserving 200,000 units, not just creating them,” Boyd said at the meeting, referring to Mayor Bill de Blasio’s “Housing New York: A Five-Borough, Ten-Year Plan.”

Citing census data, Boyd told the community board that the neighborhood was too densely populated to fit thousands more residents. She passionately opposed a proposal for rezoning that the board had submitted to the City Planning Department.

But the community board members, including Chairman Dwayne Nicholson, were visibly annoyed by Boyd’s demeanor and decided to dismiss the meeting. The meetings that followed often ended up in verbal clashes and sometimes insults.

Community Board 9 members tried to isolate Boyd as a radical who really spoke only for herself, and although a part of the community began keeping her at distance, her group kept enlisting members.

Some residents found more much in common with Boyd than they had with the community board members.

“We all want the same thing,” said Cheong, who although, unlike Boyd, favors rezoning, shares with her the goal of preventing what they regard as reckless development.

“The mayor made affordable housing a centerpiece of his agenda and this is clearly going against that,” said Cheong, who lives on Fenimore Street, referring to the luxury development that began spreading across the community with city officials’ approval.

“The politicians have sold us out,” Celeste Lacy Davis, a founding member of Prospect Park East Network, said during a Community Board 9 meeting in September. “The only thing we have left is community.”

Adams, who said his plan is to create 80,000 new units all around Brooklyn, was the first elected official to become a target of criticism.

“If they don’t preserve the current stabilized apartments, where am I going to live?” said Donna Mossman, who is the co-founder of the Crown Heights Tenant Union, a group that provides assistance to tenants who are victims of landlord harassment.

According to the Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy, a research center based at New York University, Community District 9 possesses the second-largest affordable housing stock in the entire New York City metropolitan area, with 89.3 percent of rent-stabilized units. It is preceded only by Community District 7 in the Bronx, with 91.3 percent, and is well above the second ranking affordable housing stock in Brooklyn, Community District 14, which includes East Flatbush, with 73.5 percent.

Census data show that Community Board 9 has a population of over 110,000 people, of whom nearly three-quarters are African- or Caribbean-American and 18 percent are white.

Overall, Brooklyn lost over 38,000 people of color from 2000 to 2010, around 4 percent, while the population of whites rose by over 56,000, an increase of about 6 percent, according to census data.

The numbers seem to point toward displacement of the poor, but Adams did not accept that.

“There are large numbers of African-Americans and Caribbean who have decided to return to the south,” he said during an interview at Brooklyn Borough Hall at the end of October.

“I can’t say this is the reason, unless I’m able to point to a specific report,” he added.

Coping with displacement is simply not Adams’ first priority.

He made clear he wants to develop Brooklyn, make it more attractive to investors, and turn the borough into a destination for tourists.

“I want tourists to come to Prospect Park, I want them to come to the Brooklyn Museum, the Botanical Garden. I want them eat at our restaurants, buy at our shops,” he said, adding that he has a plan to boost an economy based on mom-and-pop stores.

Adams has always been straightforward about his ambitions. During a public meeting in Crown Heights, Adams spoke in favor of large-scale housing development in the area surrounding Empire Boulevard, which brought him both favorable and hostile receptions.

“The Mayor, the BP and the Council are those we need to work with to get what we want in this neighborhood,” said Tim Thomas, a resident of Prospect-Lefferts Gardens and author of a lblog focusing of the neighborhood.

“He only comes out when it suits him,” said Sean Noel, 41, who lives in East Flatbush.

Despite criticism, Adams’s career appears to be on the rise.

He was elected borough president in 2013, running unopposed, becoming the first African-American to hold the post.

Adams had built his career based on issues important to Brooklyn’s black community. First, he patrolled the streets of Brooklyn as a police officer. In 1995, he co-founded 100 Black in Law Enforcement Who Care, an organization known for holding news conferences in which the Police Department was assailed as racist. After rising through the police ranks, he entered politics with the Democratic Party and won a seat as a state senator representing the 20th District, which includes Crown Heights, Prospect-Lefferts Gardens, as well as parts of Brownsville, Gowanus, Prospect Heights and Sunset Park.

During his six years in Albany, Adams was critical of stop-and-frisk policies, putting him at odds with Mayor Michael Bloomberg.

Because of his criticism of police tactics, Adams’ popularity grew. When time came to elect a new borough president to succeed Marty Markowitz, people largely believed Adams was the right person for Brooklyn.

Adams ended up running unopposed in the Democratic primaries after State Supreme Court Justice David Schmidt disqualified his opponent, former Councilman John Gangemi, for having submitted invalid signatures to appear on the ballot.

But a few months into his term as borough president, Adams’ pro-development position began to chip away at his image as a politician willing to oppose the status quo, at least for the activists who came to believe that he did not care about the issue of displacement.

Boyd and other members of the Movement to Protect the People began a campaign against Adams, an attempt to convince the community the borough president could not be trusted because of his ties with real estate developers.

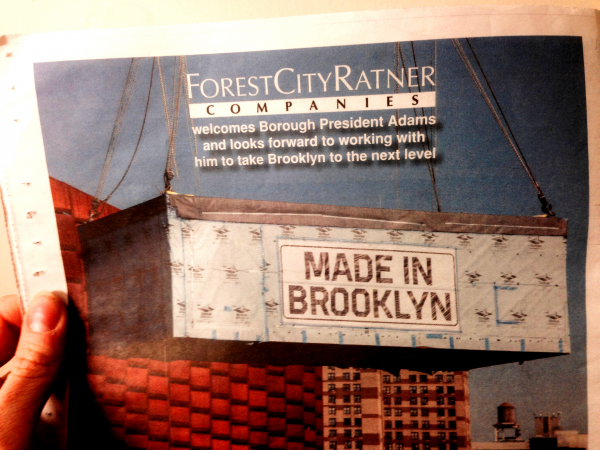

Follow The Money, an online report published by the National Institute on Money in State Politics, presents a list showing that the real estate industry was the sector that contributed the most money to Adams in his four campaigns as a state senator. Second in the list were several public sector unions.

Just from the real estate industry, Adams received almost $150,000, with at least four real estate firms donating around $10,000. East 81st Realty, which also contributed to Andrew Cuomo’s race for governor, gave Adams nearly $15,000.

When he ran for borough president, Adams received around $666,000 in contributions, according to the New York City Campaign Finance Board.

At least 15 names appearing in the list of his contributors also show up in the list of Community Board 9 members, some of whom he directly appointed, according to a list of community board members obtained through a Freedom of Information Law request submitted to the Office of the Brooklyn Borough President.

Around 70 names in Adams’s donors’ list are connected to real estate development or financing, while 12 appear to be contractors.

According to city Campaign Finance Board records, among the most generous donors were David Bawabeh of Bermuda Realty, Moishe Bergman of Penn Plaza Consultants, Yehuda Backer of the Backer Group, and Samuel Backer of BFN Realty, all of whom contributed the largest sum allowed by campaign financing laws, which is $3,850.

“I do not, nor have I ever, favor anyone or make policy based on a contribution,” Adams wrote in an email, adding that most of the contributions he received during the years came from independent individual donors.

When asked what kind of relationship he intended to maintain with the real estate industry, Adams said, “I believe it is important to work with everyone that has a stake in bettering Brooklyn,” adding again that he did not base his policies on the contributions he receives.

But someone didn’t buy it.

“That money is always going to affect whose interests they serve,” said Mark Winston Griffith, who is the executive director at the Brooklyn Movement Center, a non-profit, membership-led organization that mobilizes residents to tackle a wide range of issues affecting the community, including police brutality, sexual harassment, education and food awareness.

During a phone interview, Griffith said he wasn’t familiar with the figures in the Follow the Money’s report on Adam’s campaign, but added, “If that is accurate, then it’s a problem.”

According to Griffith, the interplay between development and politics is to be avoided.

“At the point you accept money from the real estate industry, then you are putting yourself in a position where you are going to compromise on development issues. There’s no two ways about it,” he said.

The flux of real estate money into political campaigns around the city, however, has never been so intense.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruling in the Citizens United case allowed non-profits nationwide to sponsor political candidates with large amounts of money. Jobs for New York, an independent funding committee led by the Real Estate Board of New York, donated nearly $5 million to City Council candidates “who are committed to creating good jobs, affordable housing and strengthening the middle class,” according to the mission announced on the committee’s website.

One of the largest contributions contributions went to Council member Laurie Cumbo, whose district covers part of Community Board 9 as well as Clinton Hill, Fort Greene, Navy Hill and a portion of Downtown Brooklyn. Jobs for New York’s donation to her campaign was just shy of $230,000, the city Campaign Finance Board reports.

Cumbo tried to send a message of solidarity to the constituency by showing up at a rally organized by the Crown Heights Tenants Union, and held in front of Kings County Housing Court, in Downtown Brooklyn last October, in support of a tenant who filed a civil lawsuit against her landlord that alleged repeated harassment.

“As an elected official, particularly, of color, you always have to represent or fight over these types of tactics that are being utilized to displace particularly residents of color,” Cumbo told reporters. “This wave of displacement is happening. We’re seeing the change in demographics.”

While local politicians portray themselves as reformers, community activists continue to distrust them.

“We out put these black people in power, and this is what they do: they sell us out,” Boyd declared during a forum about gentrification held at Brooklyn College in November.

As she spoke about the elected officials in Brooklyn, Boyd’s voice trembled.

“Every time one of those politicians stands up and talks about creating affordability, you need to boo their asses down, because all they are talking about is luxury development in your community, all they are talking about is moving you out,” Boyd told the audience, which included activists from all over the community who made the journey to Brooklyn College to attend the session.

“This is real,” Boyd said. “You better start making those damn politicians accountable.”

Photo, top: Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams says he supports development that creates more housing. (Brooklyn Borough President’s Office)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.