BY MARYANA AVERYANOVA

Winter break is usually a time for travel, family gatherings and celebration of Christmas and the New Year. However, for many international students in the United States, the decision to make a trip home during the holidays now involves legal and financial uncertainty.

Faced with visa rules, high travel costs, embassy delays, and advisories from international student offices, many students on F-1 visas, which allow international students to study full time in the U.S., say they are choosing to stay put this winter, even when it means spending the holidays far from home.

A computer science student from Uzbekistan studying in Los Angeles said she checked flights and visa rules multiple times before deciding not to travel. Leaving the U.S. would require a new visa application abroad, a process she described as expensive, time-consuming and uncertain.” Every time I leave, there is that worry in back of your mind about the interview,” she said. “Considering the break is only one month, it didn’t feel worth the risk.”

She is not alone. Other students shared similar worries, and all of the students interviewed for this story, including one from Uzbekistan, requested anonymity.

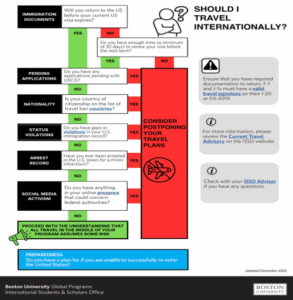

For international students, travel is not just about buying a plane ticket. Their legal stay in the U.S. depends on both immigration status and a valid visa. Most F-1 students are admitted to the U.S. for “duration of status (D/S),” meaning they may remain as long as they are enrolled full time and follow school rules outlined by the Department of Homeland Security’s Student and Exchange Visitor Program. However, the visa itself controls re-entry. Students can legally remain in the U.S. but still risk being denied re-entry if they leave. If a visa has expired, travel would trigger a required visa application abroad, a process that can take weeks or months and does not guarantee approval.

According to the U.S. Department of State, the visa processing timelines differ sharply by country and embassy, with some locations reporting limited availability or not accepting student visa appointments at all.

Adding to the uncertainty, the Department of Homeland Security has proposed changes that would replace the current duration-of-status framework with fixed admission end dates. While the proposal is not in effect, immigration attorneys say the change could require students to apply for extensions more frequently and increase the risk of falling out of status if applications are delayed or denied, complicating travel and long-term planning.

On top of that, in late 2025, U.S federal agencies also expanded social media screening for some visa applicants, requiring them to provide social media handles and adjust privacy settings to make accounts public during the visa process. Boston University’s International Students & Scholars Office warned that added screening could slow visa processing and lead to closer review for students, including students with F-1 visas.

Students’ concerns have been shaped not only by federal policy but also by guidance from universities themselves. Earlier, in December 2024, several universities urged international students to return to the U.S. before the presidential inauguration, citing uncertainty around possible immigration policy changes, according to reporting by the Associated Press.

That caution continued into 2025. On March 28, Brooklyn College’s International Student Office emailed students warning of potential federal travel restrictions and advised avoiding non-essential international travel until clearer information was available. The message cited uncertainty around visa processing, entry requirements, and possible delays that could affect students’ ability to re-enter the U.S.

Other institutions issued similar advisories. In June 2025, the University of Southern California warned some F-1 and J-1 students about travel risks following a presidential proclamation.

Boston University later warned that expanded vetting, visa delays, and the possibility of new travel bans could continue into Winter 2026.Several students said the warnings changed their travel plans.

A graduate student from Kosovo at Brooklyn College said unclear rules make travel feel stressful.“The issue that bothers many F-1 students is the chance of not getting admitted back into the country,” he said.“It feels like a gamble.”

A business student from Kazakhstan at Baruch College said she decided to stay after hearing stories of students being denied re-entry. “Many people want to go home,” she said, “but they are scared.”

A cybersecurity student from Turkey at John Jay College said he cannot travel because he does not currently have a valid visa. “Even if I could go, I wouldn’t,” he said. “The situation doesn’t feel calm.”

For some students, travel is not realistic at all. A biology student from Russia studying at Queens College said the U.S. Embassy in Russia remains closed. Renewing her visa would require traveling to a neighboring country at significant cost, with no guarantee of approval. “I wish I could spend the New Year with my parents,” she said. “But it will have to wait.”

Not all students stay because of fear. Many point to practical barriers, including airfare prices and the short length of winter break. An Indian student majoring in computer science and economics at Columbia University said flight prices were too high to justify a three-week visit. “The travel itself would take two full days,” she said. “I’d rather use that time to rest and work on a project.”

In contrast, another student from India said she plans to travel home anyway. She said she has not seen her family in over a year and felt prepared for the return. “I’m definitely still concerned,” she said, “but I’ve taken steps to make sure my return is safe. Some of my friends traveled over the summer and were able to come back without issues.”

A nursing student from South Korea at George Washington University said she will stay in the U.S. “Winter break is too short, and I want to save money,” she said. “Also, it is not really safe to travel. If immigration thinks I’m suspicious, I might not be able to re-enter.”

According to the National Association of Foreign Student Advisers (NAFSA), international students contributed $43 billion to the U.S. economy during the 2024-2025 academic year through tuition, housing, and daily expenses. For many students, that financial investment represents years of savings and family support, making the risk of being unable to return especially heavy.

Even when students say staying is the logical choice, many still feel homesick. Students described spending the holidays alone or with friends instead of family. A student from Hunter College said the winter season is difficult. “Everybody looks forward to holidays to see their families,” he said. “That makes me sad that I can’t.”

The Uzbek student shared, “Back home, we celebrate with many people,” she said. “Here, my friends are with their families.” Still, she tries to stay hopeful. “It’s not a terrible life,” she said. “Just bad timing.”

Even so, universities acknowledge that some international students will still choose to travel. International student offices advise students to confirm that passports and visas are valid, obtain updated I-20 forms, which verify a student’s F-1 status, and carry additional documents such as enrollment verification. Colleges also recommend checking visa appointment availability before traveling and allowing extra time to return. Universities note that preparation may reduce risk, but it cannot guarantee re-entry, as admission decisions are ultimately made by federal officers at ports of entry. Students are also encouraged to discuss travel plans with their international student advisors before departing.

This caution around winter travel in fact reflects larger challenges in international education that are already affecting enrollment. According to Reuters, U.S. colleges saw a 17 percent drop in newly enrolled international students in 2025, raising concerns about how immigration uncertainty is shaping student decisions.

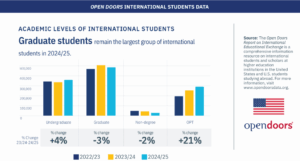

According to data from the Open Doors Report, published by the Institute of International Education, international students make up a significant share of U.S. higher education, across undergraduate, graduate, and Optional Practical Training (OPT) programs. However, federal systems do not track how many students travel during academic breaks or how many decide to stay.

For many international students, winter break has quietly shifted from a time of reunion to a period of careful decision-making. With no clear travel ban but continued warnings, students say the responsibility falls on them to decide what risks are worth taking.

This winter, many are choosing to stay.