BY KAILA MACEIRA

In 1967, Brooklyn College’s student body was 91.6% white, 4.2% Black, and only 0.8% Puerto Rican. Eight years later, after protests and sit-ins demanding representation, students helped establish the Puerto Rican Studies Department, one of the first in New York City. That legacy was celebrated this week at Encuentro: The Possible Dream, Legacies of Protest, an intergenerational event held at the Student Center that united scholars, alumni, and activists to honor more than 50 years of struggle, scholarship, and solidarity.

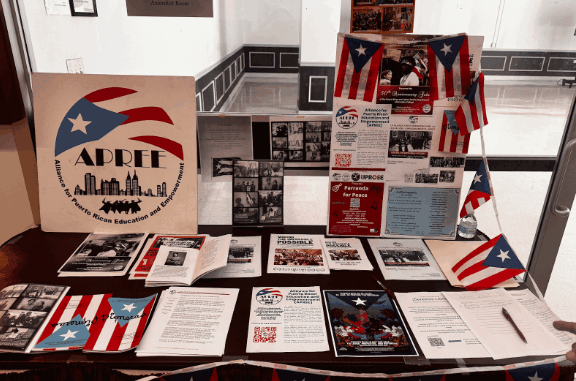

Hosted by the Puerto Rican and Latinx Studies (PRLS) Department, Encuentro brought together past and present members of the Puerto Rican Alliance (PRA), faculty, and community organizations to honor a movement that transformed the college’s identity. Today, 22.4% of Brooklyn College’s student body identifies as Hispanic/Latinx, according to Data USA.

Dr. Ruth Delgado Sánchez, one of the founding members of the Puerto Rican Alliance, recalled how early organizing began in the late 1960s, when students from across the city, Hunter, Queens, and Hofstra, traveled to Brooklyn College to unite.

“Back then, we didn’t even have Spanish in school,” Delgado Sanchez said. “We had to build everything ourselves.”

Those efforts led to the establishment of the Puerto Rican Studies Department in 1974, a landmark victory that gave Puerto Rican and Latinx students a space to learn about their history, politics, and identity. Delgado Sánchez described those early alliances as both political and cultural, with students collaborating closely with Black student groups during the civil-rights era. “We were learning about ourselves for the first time,” she said. “And that gave us power.”

Keynote speaker Dr. Johanna Fernández, a historian at Baruch College and author of The Young Lords: A Radical History, drew direct connections between that student movement and broader anti-imperialist struggles across Latin America.

“Puerto Rico was not simply poor, it was a colony,” Fernández said, explaining how U.S intervention in Latin America, from Guatemala to the Dominican Republic, displaced millions and shaped modern migration.

She urged students to see their activism as part of a longer revolutionary tradition:

“The Young Lords gave their generation the language and analysis to make sense of the trauma their parents experienced,” she said. “Their vision remains urgently relevant today, liberation will not be handed down from above, but built from below, through solidarity.”

Fernández also reflected on how she first learned about the Young Lords while researching her book The Young Lords: A Radical History. The revelation came unexpectedly.

“I was flabbergasted that I had never heard of them, even though my father almost died at the hospital they occupied,” she said, referring to the 1970 takeover of Lincoln Hospital in the Bronx. “That’s when I realized history had been erased.”

Following the keynote, a panel moderated by Professor Jasmine Mitchell showcased voices from across PRA’s history: Joe Alvarez Azario (Class of ’76), Vanessa (Class of 2006), Lex (PRA president 2021–2024), and Angelina (current president). Together, they traced the evolution of student activism from the 1970s to today.

Azario described arriving on campus in 1969 when Latino students were “so few you could count them on one hand.”

“A brother tapped me on the shoulder and said, ‘You want to know more about yourself?’ That’s how I found PRA,” he said. “It became my sanctuary.”

He recalled joining classmates in occupying administrative offices to defend the new Puerto Rican Studies program. “There was no fear,” he said. “We were fighting for self-determination.”

Vanessa, who led PRA in the late 1990s, described a thriving organization that balanced culture and activism.

“We were loud, but we were organized,” she said. “We built coalitions with the Black Student Union, the Dominican Student Association, the Haitian Student Union, everyone. Our presence alone was powerful.”

Lex, who served as president after the pandemic, spoke about a renewed wave of political pressure on student organizers.

“Before the megaphone even turned on, police were already grabbing students,” Lex said, describing protests in solidarity with Palestine. “Even when we were scared, we kept showing up.”

Current president Angelina noted that today’s challenge is institutional rather than cultural.

“Our issue isn’t that we can’t celebrate who we are, it’s repression,” she said. “Sometimes it feels like the school wishes we didn’t care about other oppressed people. But this is our college too, and we’re not backing down.”

During the discussion, one audience member proposed naming a campus building after student activists and former PRLS faculty, arguing that “if we don’t make these things visible, the administration will erase them.”

The PRLS awarded its Good Trouble Award, which honors individuals who embody the department’s spirit of resistance, to Dr. Johanna Fernández for her scholarship and activism. PRLS also named Miguel Figueroa, a PRA member and student leader, as the student recipient.

“We need to show solidarity with one another and learn from our movement elders,” Figueroa said. “Spaces like these, spaces people spent time in prison for, can’t disappear. This is our inheritance.”

Faculty described this year’s Encuentrot as an intergenerational passing of the torch, linking the department’s founders with its newest advocates. The celebration closed with a dance party featuring bachata, merengue, and salsa.