BY KAILA MACEIRA

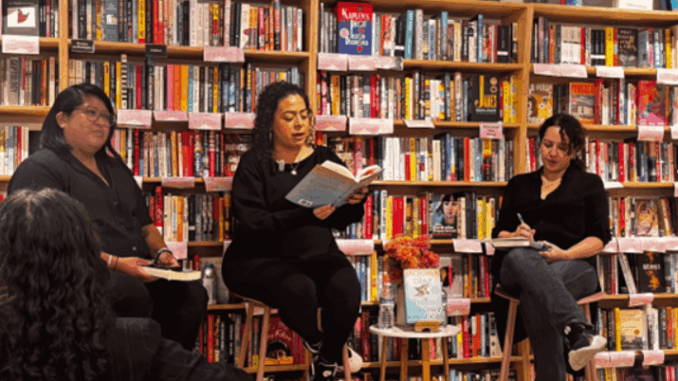

Salsa played throughout Books Are Magic, a downtown Brooklyn bookstore, as readers gathered for Puerto Rican author Jaquira Díaz to discuss her new novel, This Is the Only Kingdom.

The event, moderated by writers Lupita Aquino and Angie Cruz, marked a homecoming of sorts for Díaz, whose work often explores belonging, migration, and the blurred lines between the island and its diaspora.

Before the talk, Díaz reflected on what it meant to lose her first language after moving from Puerto Rico to Miami as a child. “I felt like I was forcibly removed,” she said. “The things that were important to me were taken away, most importantly, language.” At first she wrote in Spanish, she said, “ and then I had to come to the U.S. and learn a whole other language and write in English. It felt like I was translating myself, my memories, my culture.”

On stage, Díaz compared her novel’s structure to an old-school salsa album, where each chapter carries its own rhythm and story. “Those albums told stories and were really political and anti-colonial,” she said. One chapter was inspired by Ismael Rivera’s “Las Caras Lindas,” which celebrates Black Puerto Rican beauty. Another draws from Héctor Lavoe’s “Juanito Alemania,” a song about an outlaw she reimagined to explore moral duality. Díaz also spoke about the influence of “El Gran Barón,” calling it a groundbreaking queer salsa song that inspired themes of acceptance and chosen family. Omar Alfanno wrote the song, which Willie Colón performed.

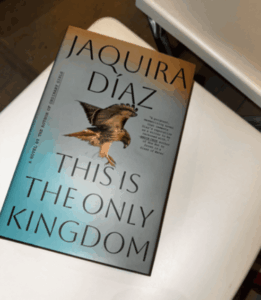

During the audience Q&A, a reader asked about the striking cover featuring a hawk. Díaz explained that a guarahau is a red-tailed hawk and serves as a symbol throughout the book. “In the story, it’s kind of a harbinger, a messenger. When I was a girl in El Castillo, guarahaus were always in the sky,” she said. “They’d swoop down and grab chicks and fly away. They were majestic and beautiful, but also dangerous.” Díaz said she worked closely with designer Greg Kulik to get the cover right.

Díaz’s work frequently returns to questions of language and identity. “Even if you don’t speak Spanish and you only speak English, there’s still a strong connection to Puerto Rico,” she said. “Spanish is a colonial language as much as English is.” No matter which language people use, “we’re still Puerto Rican. We still have a connection, not just to the culture but also to the land.”

She also spoke about a new sense of optimism among Puerto Rican youth, particularly around independence and decolonization. “College students are thinking about Puerto Rico as potentially having a different future,” Díaz said. “During Hurricane Maria, we didn’t have help from the U.S. government, we just had each other. There’s an optimism and a resilience.”

This Is the Only Kingdom arrives six years after Díaz’s award-winning memoir Ordinary Girls, which earned her a Whiting Award, the Florida Book Awards Gold Medal, and a Lambda Literary Award nomination. Her essays and fiction have appeared in The Guardian, The Atlantic, and The Best American Essays.

While Díaz has not yet published a book in Spanish, she often speaks about the role of language, translation, and cultural memory in her writing, bridging the gap between island and diaspora voices.

After the talk, Díaz signed copies for attendees who thanked her for giving voice to shared experiences. For Díaz, whose work moves between English and Spanish worlds, the evening reflected what her fiction captures best: the resilience and rhythm of a people still writing themselves home.