By ISAAC MONTEROSE

It is March 19, 1935 and Samuel J. Battle steps onto a Harlem-bound train car, bleary-eyed and hoping for a routine shift when he arrives back at the 28th Precinct station house. It has been 24 years since he broke the NYPD’s color barrier by becoming its first Black police officer and after enduring so much racism and humiliation, things were finally looking up. He was coming home from taking the captain’s exam and was fast becoming a respected police officer. However, when he stepped off the train, things were less than routine: Harlem was in chaos over rumors of the police murdering a young shoplifter named Lino Rivera in the basement of a local department store.

Much like the rioting and protesting of today in the cities of Charlotte, N.C., Ferguson, Mo., and Baltimore, the 1935 Harlem Riots did not happen over one event. Instead, it was the result of years, if not decades, of police brutality. The 28th Precinct had a history of abusing and humiliating the Black residents of Harlem, including one instance in which police brutally beat Thomas Aikens, a Black man who refused to move to the back of a bread line. Aikens was beaten so savagely that he was left blind in one eye.

Even though no body had been seen, for Harlem’s Black residents these rumors of Rivera’s death were the breaking point and were the justification for lashing out. This was the level of resentment and anger Battle would have to quell as he, Mayor Fiorello La Guardia and Police Commissioner Lewis Valentine moved to calm down the rioters and restore order. However, they were unable to convince the rioters to stop. In fact, the riots didn’t subside until the police were able to prove that Rivera was alive and well. Afterward, the city government commissioned an investigative report to find out why the riots had happened, much as authorities did in the wake of the 2014 Ferguson riots. Much like the Department of Justice report on Ferguson, this report revealed the same problems: systemic racism, poverty and police brutality.

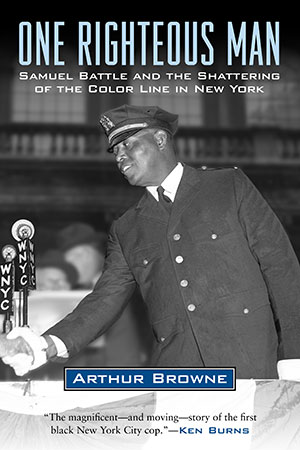

It is pretty clear that, in many ways, what had happened during these Harlem riots resembles what is still happening today. In many of these instances, there was a growing distrust and resentment between the police and the Black community it serves and in between all this are Black police officers whose perspectives are rarely heard . So when Arthur Browne, a longtime journalist at the New York Daily News, read about a ceremony commemorating Battle’s career he felt compelled to tell his story. And tell it he did in his award-winning biography, “One Righteous Man: Samuel Battle and the Shattering of the Color Line in New York.”

“What you always find when you’re a reporter, it’s your last desperate phone call that maybe is the most important one,” Browne remarked as he remembered how he first started working his book. It all began in 2009 after he read a short Daily News story about a ceremony to name a street for Battle. “I asked the Police Department who had shown up at the sign installation ceremony, thinking that anyone who was there would’ve had some interest in him, and his grandson turned out to have been there,”

Browne, who was appointed editor-in-chief of the News on Oct. 18, was the paper’s editorial page editor at the time. He found that Battle’s grandson, Tony Cherot, lived in California, and they developed a relationship. Through Cherot, Browne learned that the poet Langston Hughes had been hired by Battle to write his autobiography in 1949. But the project ended up failing when Hughes quit out of disinterest and the manuscript was unfinished. After receiving it from Cherot, Browne began the 5-year process of writing a biography that would do Battle’s life story justice.

Browne, who was appointed editor-in-chief of the News on Oct. 18, was the paper’s editorial page editor at the time. He found that Battle’s grandson, Tony Cherot, lived in California, and they developed a relationship. Through Cherot, Browne learned that the poet Langston Hughes had been hired by Battle to write his autobiography in 1949. But the project ended up failing when Hughes quit out of disinterest and the manuscript was unfinished. After receiving it from Cherot, Browne began the 5-year process of writing a biography that would do Battle’s life story justice.

Born on December 14, 1950 in Long Island College Hospital and raised in Freeport, Long Island, Browne grew up with two siblings in a middle-class home. His father, Gerald, was a motion picture cameraman and his mother, Adeline, mostly stayed at home and ran a household business that helped the families of the neighborhood get in touch with babysitters. She would also work at a department store whenever Gerald was unemployed.

Freeport was a racially segregated village, Whites on the west side and Blacks on the east side, separated by Main Street. Browne remembered the racism he grew up around: racial slurs and Black people being seen as lesser and the source of fear.

By the time Browne was finishing up high school in 1968, America was experiencing turbulent times. The war in Vietnam had become a meandering stalemate, the civil rights movement had been going on for 13 years, that year’s Democratic National Convention had devolved into mass rioting and there were constant anti-war protests. All this caused a rift between Browne’s generation and the generation that came before.

“There were many factors that led to what they used to call the ‘generation gap’ between people of my age and their parents,” Browne explained. “The racial issues that really came to the fore with the social activism, the marches in the South, Montgomery, Selma. All of those were great awakenings for many White young people. [It] was the first time that many of us saw clearly any form of African-American activism.”

Alongside all these major events, the one that still sticks with Browne was the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. Browne had run into an old classmate who was the only Black student in his grammar school. His voice began to crack as he described the painful memory. “I had not seen him because I didn’t go to the local high school. I ran into him on the street and we looked at each other and I didn’t know what to say to him. I could only say that I was sorry. It was unbearable.”

After graduating college, Browne didn’t know what he wanted to do with his life and settled on working as a copy boy for the New York Daily News. After all, he had been in the city room of the paper when he was only eight years old. Two relatives were employed in the “women’s department” at the time, and members of his family had worked at the paper for generations. The job itself was usually done by high school students and Browne’s bosses told him that it couldn’t lead to a career in journalism. But, needing a job, (and wanting to learn how a big newspaper operated) he stuck with it.

He was promoted to reporter in 1973 while still attending law school and when he first started out, his bosses gave him an ultimatum: to prove he could do the job. “Called me in and they said, ‘Kid, you are a reporter. Sink or swim, you have six months,’” recalled Browne. Forty-three years and one Pulitzer Prize later: needless to say, he swam.

In no specific order: he’s been the paper’s City Hall bureau chief, chief investigative reporter, city editor, the assistant managing editor for politics, senior managing editor, metro editor and managing editor for news. He became the editor of the editorial page in 1993.

“It’s a fantastic position,” Browne said. “It requires a great deal of discipline…it requires an intense focus on the facts … But, you’ve got to synthesize those facts into an opinion and make an argument about what you believe, speaking for the Daily News, is right for New York, for the country.” Browne would meet with other Daily News journalists on the editorial board and formulate those decisions.

While serving as editorial page editor , Browne said, he was often only generally aware of the big stories the news staff was working on. But when he happened upon the story about the naming of a street for Battle, his interest was piqued. Browne had extensively covered the NYPD throughout his career, including the tenure of the department’s first Black commissioner, Ben Ward. “It just seemed to me that, in the position that I was in, I didn’t have the knowledge that I should’ve had,” he said. “So I thought, ‘Alright, let me try to find out.’”

He started his research by going to libraries and finding old news clips about Battle but what he found is that all these stories followed a similar pattern: Battle would get hired, he’d struggle with racism and he’d persevere, rise through the ranks and eventually retire. That is why Browne saw Hughes’ manuscript as a chance to approach Battle’s remarkable story in a unique way. In fact, the manuscript and a local, long-defunct Black newspaper named The New York Age (that he found in a library) were the two main reasons his biography became possible.

“One,” said Browne, “I could not have done this without the manuscript [and] two, the difficulty was that the general newspapers at the time basically dismissed him as just another guy who came up through the ranks, retired and happened to be Black.”

Samuel J. Battle was born on January 16, 1883 in New Bern, N.C. He was the 22nd child of his father and the 11th of his mother and grew to be a large young man who was known to be a bully. Like many young Black men in the Jim Crow South, Battle had a desire to go to the comparably freer North so, when the opportunity came along, he went to New York City with his mother in 1899. He held a variety of jobs in New York from dye house worker to luggage porter. Eventually, the adventurous and headstrong Battle became interested in becoming a police officer, a job that was unthinkable for a Black man to have in early 20th century New York. However, he was not one to be deterred and after much difficulty (including one instance in which a Police Department physician lied about Battle’s heart condition) he officially became the first Black NYPD officer in 1911.

On his first day on the job, Battle walked towards his stationhouse, the 28th Precinct, and in front of it was a large crowd of Whites who stood there amazed at him as he approached. They were not only amazed at his size (Battle was 6-feet-2-inches and 260 pounds) but also at the fact that a Black man, they despised with racial slurs, was actually wearing a police uniform. It only got worse from there. In the early days of his career, Battle was by and large ignored by his White fellow police officers, often forced to patrol on his own despite being a rookie and was relegated to sleeping in what was essentially the attic of the police precinct because no one wanted to sleep near him.

Nevertheless, Battle pressed on and studied for the sergeant’s exam whenever he could. “He had the fortitude … He knew what was stacked up against him and African-Americans in general,” Browne said. “But he still said that, ‘I am me and I am entitled and they’re going to give it to me because of who I am.’” Battle knew that he had a very thin margin for error at the department and had to be twice as good as his White peers if he was going to stay an officer. With his many struggles, Battle went on to have a storied career in the Police Department that spanned 40 years. He retired in 1951 as the first Black parole commissioner. He died on August 7, 1966.

Browne said that Battle’s story can resonate today especially when it comes to matters of policing and the community. Back in the ’20s and ’30s, Browne explained, there was a pastime called the numbers game that was “very popular but it was illegal so the police would enforce the gambling laws.” In order to do so, they would barge into the homes of Black residents, often without a warrant, in search of numbers slips. “So what you have there is over-enforcement of a law disproportionately targeting African-Americans overzealously and without a constitutional basis,” said Browne. “Take that description, what am I describing? I’m describing stop-and-frisk!”

Stop-and-frisk was an extremely controversial police search tactic that was used disproportionately on young Black and Hispanic males and ruled unconstitutional in 2013 by a U.S. District Court judge. The Daily News editorial page had at one time been a strong supporter of stop-and-frisk, arguing that it helped reduce crime sharply in New York City. But after the tactic was largely dropped, the News editorial board admitted “we were wrong” because, as Browne said, statistics showed that stop-and-frisk had not really reduced crime. That became clearer when crime remained essentially level without widespread stop-and-frisk.

According to NYPD statistics, stop-and-frisk peaked in 2011 at 685,724 stops.

“It’s the same kind of thing and so you can find that kind of pattern through the book,” Browne said. “It’s just a lesson of history repeating itself and maybe if you pay attention you can say, ‘Well maybe it’s time to stop it.’”

Photo: Top, longtime Daily News journalist Arthur Browne was intrigued by the story of New York’s first black police officer, Samuel J. Battle.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.