BY EMILY SUHR

Over 13 years after the devastation of Hurricane Sandy, the waterfront community of Gerritsen Beach still suffers from the same vulnerabilities as it did during Hurricane Sandy, as residents say little has changed.

Before the storm hit in 2012, Gerritsen Beach was considered Zone B in the city’s emergency management plan. This designation was a critical factor in the neighborhood’s preparation and response to the storm, because unlike Zone A, the residents of Zone B were not instructed to evacuate when the storm came. The flooding started with people’s basements but very quickly escalated.

In the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy, then-Mayor Michael Bloomberg announced that Gerristen Beach would now be considered Zone A, and pledged better social services and improved infrastructure to prevent similar disasters in the future.

Some homeowners have since elevated their houses to fit the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) construction standards, including the base flood elevation (BFE). BFE is the height floodwater is expected to reach during a base flood, which has a 1% chance of occurring any given year. This is true for resident Barbara Curran, who lost her house due to flooding during the storm. She said it took roughly five months to rebuild and elevate her home, but that it worked.

“Since we elevated our house we haven’t had any flooding,” said Curran.

Her house used to be below sea level, something that many people in the neighborhood still struggle with. “Many homes with basements continue to flood during heavy rain or coastal storms,” said Curran.

Since Gerritsen Beach was not originally part of Brooklyn’s floodplain, “…[houses] were not built to current flood resilient construction standards provided by FEMA and reflected in the New York City Building Code,” according to the Department of City Planning (DCP).

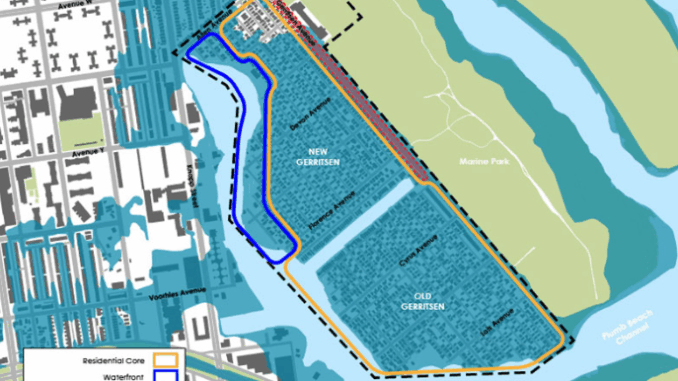

A proposal to rezone Gerritsen Beach under the DCP’s Resilient Neighborhoods initiative entered public review in October 2020, but there haven’t been any updates since then. DCP did not respond to inquiries about the plan’s status.

According to Community Board 15 Chairperson Theresa Scavo, the proposal appears to have stalled completely. “We were promised DEP [Department of Environmental Protection] sewer shut offs as well as generators for the stores on Gerritsen Avenue and many other updates. But, as far as I remember nothing has been done,” said Scavo.

She added that no significant action was ever taken. “City Planning proposed how Gerritsen should be zoned and elevation heights but only a few houses have followed the plan,” said Scavo.

The reason for this is straightforward: “The cost for floodproofing is very high. Most homeowners can’t afford it,” said Scavo.

With elevation out of reach for many residents, some advocates are pushing for alternative strategies to reduce flooding. One option, permeable pavement, uses alternative materials designed to soak up storm water and prevent flooding. At a Town Hall meeting at Brooklyn College on Oct. 22, permeable pavement advocate Rona Taylor, Executive Director of the Central and South East Brooklyn Community Development Corporation (CXSE BK), described how it would work.

“It’s a type of pavement where when it floods, the water can go into this material and then it absorbs the water and then when it’s hot, the water evaporates and it cools the air,” said Taylor.

The first implementations of permeable pavement were installed in South Brooklyn over the summer, but there have been no announcements of where it may be installed next.

For a waterfront neighborhood like Gerritsen Beach, such infrastructure could offer relief. But implementing permeable pavement would require extensive construction and major funding, both of which remain uncertain.